“…the worst idea since Greedo shooting first.”

In re Star Wars, about which every male born since, oh, 1965 or so, has a burning opinion he will share with you at the drop of a hat, Confucius* says: Every movie since the first has been worse. Lawrence Kasdan’s direction makes Empire look more sophisticated than Star Wars, but it’s not. It’s where the rot sets in. “Luke, I am your father,” is the hinge at which the bottom falls out, and it turns into reductive, b.s., Joseph-Campbell-smoking, pretentious crap. (And I say this as one who enjoyed Ewoks as a kid.)

In re Star Wars, about which every male born since, oh, 1965 or so, has a burning opinion he will share with you at the drop of a hat, Confucius* says: Every movie since the first has been worse. Lawrence Kasdan’s direction makes Empire look more sophisticated than Star Wars, but it’s not. It’s where the rot sets in. “Luke, I am your father,” is the hinge at which the bottom falls out, and it turns into reductive, b.s., Joseph-Campbell-smoking, pretentious crap. (And I say this as one who enjoyed Ewoks as a kid.)

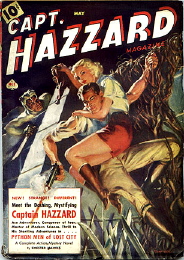

George Lucas, I’ve held on the evidence of Star Wars and Raiders, is a Great Hack. An inspired genius, of sorts, when it comes to throwaway pulp material. But, like almost all hacks, he’d rather be an artiste. And that’s where the trouble came in. Once it all had to Mean Something, he resorted to all sorts of schematic and philosophical junk that was as out of place in his weightless, zippy worlds as a tarantula on a slice of angelfood (to borrow from a serious writer masquerading as a hack). In a perfect world, Lucas would have been cranking out lots of lower-budget Indy sequels, adapting the Phantom, Shadow, and Flash Gordon, and inventing his own new heroes of different ages and places. Instead, isolated from reality by the enormous amount of money he earned by (among other things) presciently retaining the merchandising rights to Star Wars, he sat around like an egomaniacal college sophomore, filling notebooks with Deep Thoughts and working them into his movies. And the leaden demi-profundities crushed the crystalline cleverness. (Then again, at least he never put that sentence in a movie. Still, I’ll take it over “Duhhhh, I hate sand.”) The single moment of wit recalling the wry, humane humor of Star Wars in The Phantom Menace was the Tusken Raiders taking potshots at the pod racers. And that’s where I got off.

Anyway, some years ago, I was very gratified to come across the following article by the late Richard Grenier (who wrote a very funny novel in addition to his journalism), in which he recounted his contemporary notes of Lucas’s speaking about Star Wars, which jibed perfectly with my childhood memories—that it was just a fun homage to the old serials of Buster Crabbe, et al.—which I’d begun to doubt over the years with Lucas’s insistence that it was an epic plot cycle conceived ab initio in nine parts. With apologizes that Blogger doesn’t easily provide for cuts to hide it behind, your Volgi presents it here for your edification and perhaps discernment of the the seeds of Lucas’s pretension. Art movies? Like THX 1138? (Is the Volgi alone in always being amused that the cops’ motorcycles sound exactly like TIE Fighters?)

Anyway, some years ago, I was very gratified to come across the following article by the late Richard Grenier (who wrote a very funny novel in addition to his journalism), in which he recounted his contemporary notes of Lucas’s speaking about Star Wars, which jibed perfectly with my childhood memories—that it was just a fun homage to the old serials of Buster Crabbe, et al.—which I’d begun to doubt over the years with Lucas’s insistence that it was an epic plot cycle conceived ab initio in nine parts. With apologizes that Blogger doesn’t easily provide for cuts to hide it behind, your Volgi presents it here for your edification and perhaps discernment of the the seeds of Lucas’s pretension. Art movies? Like THX 1138? (Is the Volgi alone in always being amused that the cops’ motorcycles sound exactly like TIE Fighters?)

*For those who came in late: 孔夫子 means Confucius, the given name of your Œcumenical Volgi (pictured above right).

January 17-19, 1997

Is ‘Star Wars’ the movie of doom?

By Richard Grenier

THE WASHINGTON TIMES

Is it the end? Are we doomed? Ever since the super-blockbuster series “Star Wars” was unleashed upon the world 20 years ago, have we been on the downward slope? Has it been all cheap thrills? Big money? No plot? No common sense? Was “Star Wars” the movie that destroyed Hollywood? Will the film’s technically revamped version to be released next week sound Hollywood’s final death knell? Or will Newsweek, which performed a magnificent mea culpa over Paula Jones just last week, owe us another mea culpa?

As I write, after all, a Hollywood movie leads the box office listing of every city of the known world. How about Shanghai? In Shanghai, Chinese movies really die, but Hollywood movies go through the roof.

As a rough rule of thumb, routine American movies used to make their money back in the U.S., while action movies went wild abroad, grossing double what they grossed at home. It’s often thought that the buying up of Hollywood studios by giant companies has created a profit consciousness the studios never had before. But from my experience Hollywood studios have always loved money—much as any successful company. And when film studio executives scrutinized their account sheets in this new age, and saw the money brought in by blockbuster action movies, they felt a stirring of the soul, and the industry entered a whole new phase.

In the last decade, the cost of making a movie went up and up—$20 million, $40 million, $80 million—but as long as the films brought in enough money to cover the outlay, flowers bloomed and birds sang in the trees.

But film company executives soon found that “Star Wars,” along with “Jaws,” had locked Hollywood into a real blockbuster mentality. Production figures that used to terrify executives did so no longer and they began swinging for the fences at every pitch. The small, modestly profitable film was out of the game. Moreover, along with the blockbuster action film that could easily gross $200 million, there developed a parallel industry in products carrying the film’s logo—toys, lunch boxes, soundtrack albums—that could bring in many millions more.

“’Star Wars’ irrevocably altered Hollywood esthetics,” pronounced Newsweek. “What [George] Lucas inaugurated was the triumph of kineticism over content, action over plot, comic-book simplicity over real-life complexity, and special effects over all. Lucas took his tempo from adolescent metabolism, and it was impossible to turn back the clock after that. And the jolts of adrenaline have been coming in ever faster intervals.“ ”‘Star Wars’ was the end of “one of the most fertile and exciting eras in the history of Hollywood filmmaking,” wrote Newsweek, apparently referring to the 1960s and early 1970s. But now “Star Wars” and its progeny have gone and ruined it all.

Now I personally don’t remember “The Great Spider Invasion,“ ”The Singing Nun,“ ”The Pom Pom Girls,” or “The Crater Lake Monster”—all made at the height of this fertile and exciting era of Hollywood filmmaking. But I’ve a feeling that they were absolute clinkers. In the present decadent era, on the other hand, in just this past year, we’ve had “The English Patient” and Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible.” Were these films still immersed in what Newsweek considers the post-“Star Wars” “depths of adolescent metabolism”? For that matter, just what is “adolescent metabolism?” A judgment like that requires some thought.

Whatever it is, it’s sold countless videocassette versions, best-selling Bantam novelizations, $4 billion in “Star Wars” merchandise, and is responsible for 963 sites on the World Wide Web, fan clubs, and innumerable collectibles. And this from a movie for which its author had no great hopes. Mr. Lucas has changed his account a bit since the series’ stupefying success, but I’ve the tape of an interview he gave on the eve of the first film’s opening on Memorial Day, 1977.

“Star Wars” had no real story, he said then, but was a mere “composite” of all the action comic-books he’d read as a child. It was a brainless “kid” movie, he confessed modestly. He just hoped it would be successful enough so he could live off the proceeds of a “Star Wars” series made specifically for children while he made small-audience art movies, which were more to his taste. He confessed shyly that he felt he had no gift for mass entertainment—which is an interesting attitude coming from a man whose “Star Wars” trilogy has by now taken in worldwide no less than $1.3 billion. “Star Wars” is the most lucrative Hollywood franchise since Snow White moved in with the Seven Dwarfs, and beginning on January 31 vast mobs of youngsters are expected to line up at movie houses across the country—youngsters some of whom weren’t even born at the time of the picture’s initial release.

The deep thinkers of Hollywood don’t all agree as to the meaning of the phenomenal success of “Star Wars,” by the way. Steven Spielberg (”Indiana Jones,“ ”Schindler’s List”), quite a successful mass movie director in his own right, feels that the appearance of “Star Wars” was “a seminal moment when the entire film industry instantly changed,” recognizing “the value of childhood.” But George Lucas, rising above his comic book beginnings, now says he’s “spent a great deal of time looking at history, philosophy, and mythology, and about how those relate to the breakdown of a democracy and the rise of a dictator.”

So you see how it is in America? You start making movies for kids and the next thing you know you’re a major political thinker.

Published January 17 - 19, 1997, in The Washington Times

Copyright ©1997 News World Communications, Inc.

Don’t ask impertinent questions like that jackass Adept Lu.