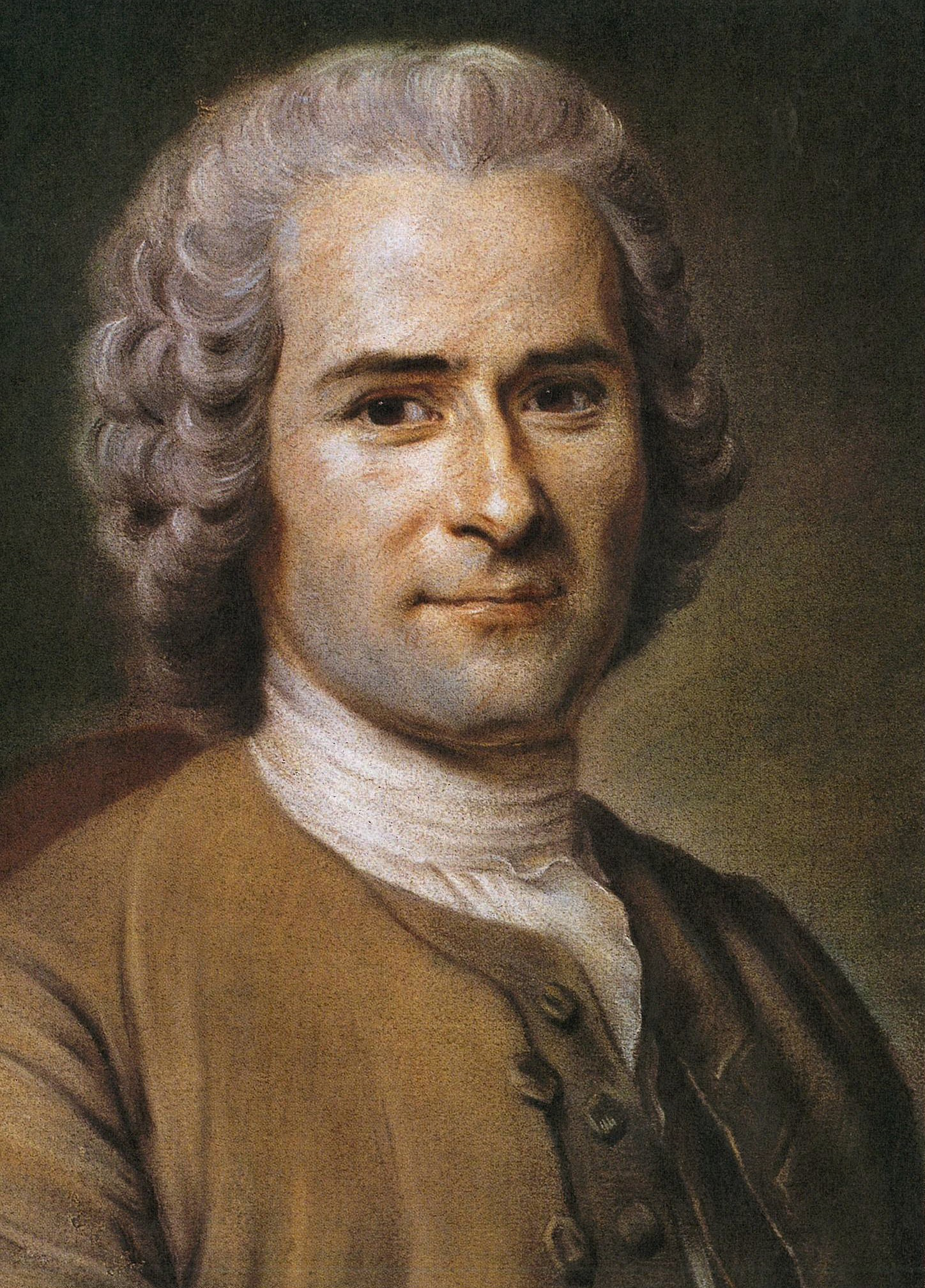

What’s the Matter With Kids Today? Or, Rousseau was “deceitful, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and full of malice.” —Diderot

Over in the Corner, Jonah Goldberg got flamed by some guy who seems to want to exculpate Rousseau, “smart people,” and “intellectuals” from murderous frenzy of the French Revolution. The historical nuts and bolts come later. Feel free to skip them. But your Œc. Vol. has a point on contemporary culture.

Over in the Corner, Jonah Goldberg got flamed by some guy who seems to want to exculpate Rousseau, “smart people,” and “intellectuals” from murderous frenzy of the French Revolution. The historical nuts and bolts come later. Feel free to skip them. But your Œc. Vol. has a point on contemporary culture.

In the guy’s screed, one detects a the tribalist, reflexive defense of “smart people” and “intellectuals.” This, one suspects, is a really big, if undiscussed factor in a lot of the problems the Right has with the young, educated crowd. High schools and universities have generally become so ideologically monolithic that left-wingery is not seen as one set of propositions about human nature and societal organization competing against others, but the settled wisdom of the ages with which all “smart people” agree. Those who don’t (benighted mom and dad, the folks back in Terre Haute, etc.) are ignorant or prejudiced, or evil. (Because why else oppose the Correct? Which is really a way of expressing “the Good” without using traditional religious or moral vocabulary.)

Plus, the kids who come in are often times high on themselves and their SAT scores and have increasingly not been exposed to alternative moral systems, like traditional religion, in which they’d hear, “Yeah, you’re smart, but so what? Are you good?” Or have pointed out to them that not a few brilliant men have gone on to do profound evil. So they think of themselves and their unconsidered philosophy as those entitled to rule in a more just world. They’re smarter than everyone else—the SAT said so!—and intelligence is the sole criterion of worth they’ve been held to. They go to the best schools which are often echo chambers of the intelligence-über-alles ethic and learn What Smart People think and consider themselves Intellectuals (without ever running across the pejorative origins of the term, which contrasted with “scholar”), emerging as unconscious, smug élitists and natural Progressives.

It’s a whole metaphysical orientation. It’s got its religious virtues (fairness! equality!), theology (race! gender! class!), its in- and out-groups (the Good & Smart! the Dumb & Mean!), etc. A lot of these kids will get jobs and wake up. But a lot of them, especially the engagés who gravitate to politics, won’t. And one’s political views rarely change after the age of thirty. As said, this is a serious problem for the Right.

On to the historical nitpickery. Laughably, the guy defending the tribe of smart people and exhorting Goldberg to read has either apparently never picked up a history book himself or is so deluded that “smart people” always do the right thing by definition that he completely mischaracterizes the French Revolution. On to his aggressively posed questions designed to pin Goldberg under the weight of his own shatteringly recognized ignorance.

On to the historical nitpickery. Laughably, the guy defending the tribe of smart people and exhorting Goldberg to read has either apparently never picked up a history book himself or is so deluded that “smart people” always do the right thing by definition that he completely mischaracterizes the French Revolution. On to his aggressively posed questions designed to pin Goldberg under the weight of his own shatteringly recognized ignorance.

What “smart people” were led to believe that there was a moral and philosophical justification for slaughter during the French Revolution?

Uh, Robespierre. Hébert. Danton. Marat. Billaud-Varenne. &c. &c. &c.

Does Robespierre count as some kind of “intellectual?”

Hell and yes. Here’s the beginning of his entry in the Literary Encyclopedia:

The child of provincial lawyer in Arras, Robespierre was marked by the early death of his mother and abandonment by a father who left him with his brother to be raised by grandparents. Intelligent and disciplined, Robespierre received a grant to study at the prestigious Collège Louis-le-grand in Paris and went on to receive a degree in law. He returned to Arras where he distinguished himself as a lawyer and was soon appointed judge in the diocesan court and first to membership and then to the presidency of the Arras Academy for the Advancement of the Arts and Sciences. A lucid philosophe inspired by Rousseau, Robespierre wrote a prize-winning “Mémoire sur les peines infamantes” [“Report on Degrading Punishments”] and argued for reforms that would ease the lot of the poor.

The child of provincial lawyer in Arras, Robespierre was marked by the early death of his mother and abandonment by a father who left him with his brother to be raised by grandparents. Intelligent and disciplined, Robespierre received a grant to study at the prestigious Collège Louis-le-grand in Paris and went on to receive a degree in law. He returned to Arras where he distinguished himself as a lawyer and was soon appointed judge in the diocesan court and first to membership and then to the presidency of the Arras Academy for the Advancement of the Arts and Sciences. A lucid philosophe inspired by Rousseau, Robespierre wrote a prize-winning “Mémoire sur les peines infamantes” [“Report on Degrading Punishments”] and argued for reforms that would ease the lot of the poor.

In March 1789 Robespierre was elected to the Etats généraux as a representative for Artois and made significant contributions to the drafting of a new constitution by the infant National Assembly. A highly effective orator, who convinced by reason rather than demogoguery, Robespierre became more and more influential in the revolutionary debates, arguing for the rights of the common people, universal suffrage, respect for all races and creeds, and against the powers of the rich, the aristocrats and monarchs. His arguments were much assisted by the fact that in his personal life he disdained comfort as well as luxury, earning him the soubriquet “the Incorruptible”, even as they contributed to a certain wariness on the part of those who ran the Assembly. As the political temperature rose during 1791, Robespierre sided more and more openly with the common people and earned the loyalty of Parisians for his courageous refusal to yield to those who sought to restore the monarchy.

Robespierre was a convinced Deist and worked assiduously to create a society believing in one supreme being, source or all moral and civic virtue, a virtuous republic of small property owners [Rousseau again —Œc. Vol.] and became the moral conscience of the Club des Jacobins. Following the overthrow of the monarchy on 10th August 1792 and the massacres of 2-6th September 1792 he was elected to lead the delegation for the Commune of Paris in the National Convention and was among those who called for the execution of Louis XVI during his trial in December 1792.

And what the f**k do you mean by “erase society?”

That’d be the Revolution’s attempts to abolish Christianity, the aristocracy, any social distinction between individuals, the whole freaking calendar, etc.

That’d be the Revolution’s attempts to abolish Christianity, the aristocracy, any social distinction between individuals, the whole freaking calendar, etc.

Returning to Rousseau, if you think this is unrelated to “man is born free but is everywhere in chains,” you’ve been hitting the philosophy bong. The anti-Judeo-Christian idea of the innate virtue and goodness of people which is only perverted by evil societal institutions remains the Ur-complaint of the Left. The logical conclusion of this—which the very smart philosophies of the Revolution divined—is that everything must be reformed, made new, abolished, or exterminated.

Goldberg’s correspondent continues patronizingly:

I think you’ll find he was a pretty clear and limpid writer, and even a cursory glance at The Social Contract should show you that his political ideal was the small city-state of responsible, often-participating citizens, not the Committee of Public Safety.

Hey, someone took Philosophy 101! Curiously, despite all this, Rousseau’s most dedicated followers produced not only the Terror but a variety of nasty, coercive régimes throughout history, right down to Sorbonne student Saloth Sar who idealized the peasantry of his native land as Rousseau’s bon sauvage and set about destroying all the corrupting elements around them under his nom de guerre, Pol Pot. Why did the French-educated Khmer Rouge establish Year Zero? Because they wanted to start all over in a state of freedom and virtue. Not least because Rousseau said they could. That they had to build a mountain of skulls to do so was of no consequence. Eggs, omelettes.

Goldberg’s correspondent seems to tell us Rousseau can’t be held responsible for these evil men misinterpreting his innocuous, Reasonable words. Reluctantly, we must conclude that the guy is either illiterate or a fool. Let’s turn to the Social Contract for just a second. What is the relationship between an individual and the state?

Goldberg’s correspondent seems to tell us Rousseau can’t be held responsible for these evil men misinterpreting his innocuous, Reasonable words. Reluctantly, we must conclude that the guy is either illiterate or a fool. Let’s turn to the Social Contract for just a second. What is the relationship between an individual and the state?

The State, in relation to its members, is master of all their goods by the social contract, which, within the State, is the basis of all rights.

And:

The citizen is no longer the judge of the dangers to which the law desires him to expose himself; and when the prince says to him: “It is expedient for the State that you should die,” he ought to die, because it is only on that condition that he has been living in security up to the present, and because his life is no longer a mere bounty of nature, but a gift made conditionally by the State.

The State is a priori the source of all rights, including your right to live. Clear and limpid!

The “responsible, often-participating citizens” are disposable slaves of the State, the General Will, and, therefore, the philosophes who can divine it. Woody Allen’s Socrates kept clearing his throat and pointing at himself when invoking the concept of “philosopher-king,” and here one senses a reason intellectuals like Rousseau. He makes them God. As a teacher of some of the Gormogons once quipped, “So there’s Lenin, poring over his Marx in Switzerland, and he runs across the phrase ‘dictatorship of the proletariat.’ He perks up. ‘Dictatorship? Needs a dictator. Sign me up!’”

In addition to pandering to their sublimated desires to rule like gods (as they are entitled and only denied by unjust, evil society), Rousseau is like catnip to soi-disant intellectuals and political idealists, because he affects two attitudes that appeal powerfully to them: universal beneficence and the ability to reason one’s way to utopia from first principles (which is to say hypocrisy and hubris). This “we just love everyone, and we can sit at our desk among our books and reason our way to Helping Them” aura is an intoxicating miasma around his works. In terms of politics, Rousseau is marked by a certain incoherence at first, but eventually, when he gets around to elaborating the General Will and the State which embodies it, he lays the foundations of not merely dictatorship but totalitarianism.

In addition to pandering to their sublimated desires to rule like gods (as they are entitled and only denied by unjust, evil society), Rousseau is like catnip to soi-disant intellectuals and political idealists, because he affects two attitudes that appeal powerfully to them: universal beneficence and the ability to reason one’s way to utopia from first principles (which is to say hypocrisy and hubris). This “we just love everyone, and we can sit at our desk among our books and reason our way to Helping Them” aura is an intoxicating miasma around his works. In terms of politics, Rousseau is marked by a certain incoherence at first, but eventually, when he gets around to elaborating the General Will and the State which embodies it, he lays the foundations of not merely dictatorship but totalitarianism.

Stepping back from his perfumed theory, let’s see what Rousseau wrote when given the chance to concretely instantiate his philosophy, here in the Constitutional Project for Corsica (that is, the short-lived Corsican Republic, 1755–1769).

Cutting through a lot of his historical-philosophical wankery we have:

- Abolition of money (A four-thousand year regression): “…exchange can…be effected in kind, without intermediary assets, and it will be possible to live in abundance without ever handling a penny.”

- A centrally supervised economy: “…it would be possible in each county town to set up a public double-entry register, where private individuals each year would have recorded, on one side, the nature and quantity of their surplus products, and on the other side those they lacked. By balancing and comparing these registers from province to province, the price of produce and the volume of trade could be so regulated that each county would dispose of its surplus and satisfy its needs without deficiency or excess, and almost as conveniently as if the harvest were measured to its needs.”

- Mind-boggling economic illiteracy: “As long as you confine yourselves to this [system described above], trade will remain in balance; and exchange, being regulated solely according to the relative abundance or scarcity of produce, and the greater or lesser facility of transport, will everywhere and at all times remain on a basis of proportionate equality; and all the products of the island, being equally distributed, will adjust themselves automatically to the level of the population.”

- Deliberate reduction of trade (and therefore wealth): “…this system of administration, once established, will become easier every year, not only as a result of experience and practice, but also by reason of the progressive diminution of trade which must necessarily follow, until it has been reduced of its own accord to the smallest possible volume, which is the final goal we ought to envisage.¶ Everyone should make a living, and no one should grow rich; that is the fundamental principle of the prosperity of the nation; and the system I propose, so far as in it lies, proceeds as directly as possible toward that goal. Since superfluous produce is not an article of commerce, and is not retailed for money, it will be cultivated only to the extent that necessaries are needed; and anyone who can procure directly the things he lacks will take no interest in having a surplus.”

- Defiance of history: “ It may be feared that this economic system would produce an effect contrary to my expectations; that it would tend to discourage rather than to encourage agriculture; that the farmers, deriving no profit from their produce, would neglect their work, that they would confine themselves to mere subsistence farming, and that, without seeking prosperity and content with raising an absolute minimum for their own use, they would let the remainder of their land lie fallow. This is apparently confirmed by the experience of the Genoese government, under which the ban on the exportation of agricultural produce had precisely this effect. ¶ But it must be remembered that, under this administration, money was the prime necessity… [blah blah blah]”

- Central planning of occupations: “Although we must be careful to reject the idle arts, the arts of pleasure and luxury, we must be equally careful to favour those which are useful to agriculture and advantageous to human life. We have no need for wood-carvers and goldsmiths, but we do need carpenters and blacksmiths; we need weavers, good workers in woollens, not embroiderers or drawers of gold thread.”

- Pretense to omniscence in requirements: “Corsica, by starting earlier, would not have the same danger to fear; a strict system of forest control must be set up in good season, and cutting so regulated that production equals consumption.”

- Autarky: “I suspect that these establishments, if well managed, will be able to ensure all the necessaries without requiring any foreign imports at all…”

- State power: “ But it is not thus that I envisage the sinews of public power. On the contrary, I want to see a great deal spent on state service; my only quarrel, strictly speaking, is with the choice of means.…”

- Proto-Communism and totalitarianism: “ Far from wanting the state to be poor, I should like, on the contrary, for it to own everything, and for each individual to share in the common property only in proportion to his services.… But, without entering into speculations which would take me too far afield, it is sufficient here to explain my idea, which is not to destroy private property absolutely, since that is impossible, but to confine it within the narrowest possible limits; to give it a measure, a rule, a rein which will contain, direct, and subjugate it, and keep it ever subordinate to the public good. In short, I want the property of the state to be as large and strong, that of the citizens as small and weak, as possible.”

- Finance the state through coercion—collective farming, heavy taxes on the Church, and forced labor: “ I know that there is a large quantity of excellent land still lying fallow on the island, land of which the government could easily make use… [I]t will only be necessary to double the ecclesiastical tithe and then take half of it… [Using men’s] labour, their arms and their hearts, rather than their purses, in the service of the fatherland, both for its defence, in the militia, and for its utility, in corvées on public works.

- Social levelling through compulsory dress (perhaps a Mao suit?): “Enact sumptuary laws, therefore, but make them always more severe for the leaders of the state, and more lenient for the lower orders; make simplicity a point of vanity, and arrange things so that a rich man will not know how to derive honour from his money.”

- Delegitimization of earned wealth, exaltation of political power: “Civil power is exercised in two ways: the first legitimate, by authority; the second abusive, by wealth.”

In addition, every citizen would be required to take an oath pledging, “I join myself—body, goods, will, and all my powers—to the Corsican nation, granting to her the full ownership of me—myself and all that depends upon me.”

Rousseau was, as noted smart guys Voltaire and David Hume said, “a monster of vanity and vileness,” and “a monster who saw himself as the only important being in the universe.” He continues to appeal to those equally convinced of their own virtue and centrality to the cosmos.

Don’t ask impertinent questions like that jackass Adept Lu.