Ominous fingerpost for religious liberty

Houston has subpœnaed a bunch of pastors’ sermons in the name of “non-discrimination.” Confucius* holds no particular brief for these pastors or whatever they might preach, but finds it more than a little troubling that enough government employees considered it a good idea to issue such a subpæna.

Houston has subpœnaed a bunch of pastors’ sermons in the name of “non-discrimination.” Confucius* holds no particular brief for these pastors or whatever they might preach, but finds it more than a little troubling that enough government employees considered it a good idea to issue such a subpæna.

Francis Cardinal George, the retired (and dying) cardinal archbishop of Chicago, rather famously said, apropos the increasing aggression of our secularizing culture, “I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison and his successor will die a martyr in the public square. His successor will pick up the shards of a ruined society and slowly help rebuild civilization, as the church has done so often in human history.” This subpœna adds a tiny ring of prophecy to the Cardinal’s words. (For the context, and his denial of any prophetic intent, see here.)

When the ruling class finds raisons d’état to attack its subjects’ religion (and we’re being treated as subjects here, not citizens), they are always increasingly frustrated—because religion is not merely stronger than politics, it resists the latter. If the rulers don’t give up, eventually persecution sets in. Are we there yet? No, but these acts of harassment bespeak the hostility which could eventually fuel measures more serious than cavalierly bankrupting bakers for their scruples in frosting preferences.

What would this look like? Well, as it happens, there’s a very readable book just out called God’s Traitors: Terror & Faith in Elizabethan England which depicts in detail, following a particular family down the years, the measures and cruelties dealt to those who held to traditional Christianity in the face of the established church. Aside from the zealots on the fringes, neither side really desired to escalate the conflict—most Catholics were happy to be civilly obedient to Elizabeth, and the government did not start out looking to stamp out Catholicism. However, the logic of the situation—and the identification of state and established religion—drove both groups to increasingly extreme behavior.

Americans, in our public culture, are children of Britain and until very recently have been largely (when not vehemently) sympathetic to the narrative of Protestant enlightenment driving out Catholic superstition, backwardsness, and foreignness. This grand narrative—without minimizing the intellectual achievements brought about in Britain during its Protestant heyday**—and the natural human tendency to valorize the victorious tends to elide over the plight of everyday people trying to practice their religion as their forebears did and emphasize the villains and assassins the losing side produced, while eliding the cruelties and emphasizing virtues of the winning side.

The danger in our situation is that the “culture war” in our society has increasingly driven the religious to one side and the anti-religious to the other. Both of these groups have mutually exclusive claims about the nature of life; the revolutionary side has pushed legislation and enacted judicial degrees to have their morals enshrined; and now seems invested in painting policy opponents as wicked. The traditionalist side has fought back in kind, and we seem to be entering a similarly polarized spiral into mutually incompatible claims about the nature of citizenship.

One lesson from Elizabethan England is this: if you hold the high institutional grounds, you can win. You can marginalize your opponents and gradually convince the bulk of the citizenry that they are suspect in their loyalties and harbor wicked designs on the polity (as indeed some of them inevitably will as they become convinced the polity is bent on the destruction of the Good). For traditionalists—particularly the religious—this should stand as a dire warning.

Given the ascension of angry secularism as the invisible religion of the Left and its increasing function as the moral lodestar of the Democratic Party, media, academia, much of the judiciary, etc., Protestants as well as Catholics, Jews and Muslims and Buddhists and Hindus, should very much worry that they could find themselves in a position analogous to that of English Catholics in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

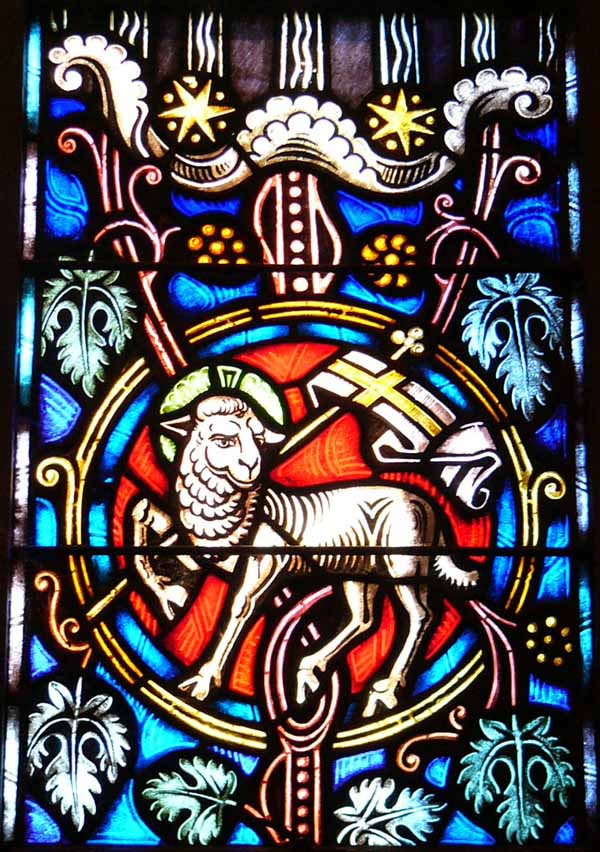

Worried about this? Might Confucius suggest a symbol appropriate to Christian concern is the Lamb of God. This symbol on a medallion was one of the many bits of “popery” outlawed by the Elizabeth authorities. Given its impeccable scriptural provenance, our Protestant brethren could also embrace it as a symbol of the Christian Church under duress.

*For those who came in late, Confucius has the pleasure to serve as the Gormogons’ Volgi Œcumenicæ, or Œcumenical Volgi. ’Puter also visited him last week, but the Volgi is unutterably dull and their doings therefore not worthy of recounting. Though a Lambeau Leap may or may not have been involved.

**The Volgi thinks the two are less closely tied than, say, Daniel Hannan in his recent work, but leaves the correlation-causation dispute for another day.

Don’t ask impertinent questions like that jackass Adept Lu.