False Flag Operations

As the Czar discusses the Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, this will be less of a movie review and more of a jeremiad about social media.

As the Czar discusses the Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, this will be less of a movie review and more of a jeremiad about social media.

By now, you’ve heard, through Facebook and Twitter, that the Ryan Gosling movie gets all of its history wrong, and is an insult to the brave Americans who finally, after much hard work, put an American flag on the moon. Specifically, the planting of the American flag on lunar soil is deliberately omitted from the picture, as are any depictions of our flag on the Saturn rocket, so as not—the Czar heard—offend the Chinese when the movie plays there.

The Czar heard from a different source—someone who actually saw the movie—that this isn’t quite true. See it, we understood, and you’ll see this is another outrage contagion by social media.

Readers on our Twitter feed will probably not recall, but the Czar avoided commentary on this topic, and last night, he and the Царица went to a local, first-run theater that had probably less than fifty adults in it, a Gen Xer with a small child, and a couple of millennials who had a very difficult time turning their phones off in a dark theater.

This movie is not over-the-top jingoistic, but it ranks in our book as a highly patriotic film. Here are your spoiler-free facts:

- The movie does not, in fact, show the planting of the flag. More specifically, it does not show the difficulty Aldrin and Armstrong had trying to unfold the spring-loaded device, the fumbling with trying to get it into the lunar soil, and the problems getting it to stay upright—facts which are generally not known because the ground team didn’t want it to look like they were jackasses up there. The movie skips over this somewhat embarrassing event.*

- In several shots that follow, as Armstrong stares in wonder at the “magnificent desolation” of the lunar surface, you see the flag deployed.

- American flags are all over this film, including many close-up shots of the flag on the side of the Saturn V rocket.

- There’s even a gigantic flag painted on the side of the assembly building that the Czar understands wasn’t there in 1969, but was applied to the side of the building in 1976.

- There are numerous references to American ingenuity and bravery, pretty much from the get-go and all the way to the end, when the film just about wraps up with historical video of a French woman saying she knew the Americans would succeed, as soon as she heard America wanted to go to the moon—who else could do it?

- There are also references to protests and liberal kvetching about the cost of the missions (in both dollars and lives), but these play out mostly in the background. They are present, but given scant focus.

- As a shot to the Chinese markets, there’s a blatant scene of Communist Chinese cheering for America when Armstrong puts hits foot on lunar soil.

There are more examples of patriotism in the movie, but these are too numerous to list. Trust the Czar—this movie is very cognizant of American patriotism and bravery, and does not short-shrift it. Please, see this film.

In short, the movie is good, if not actually borderline great. The first third of the movie seems to be a continuous string of fast-moving scenes that connect 1961 to 1969, but there’s a payoff to nearly every vignette, so be patient with it. The film is perhaps the first to simulate for the audience (to varying degrees of realism, though) what a rocket launch is like inside the capsule from countdown to orbit. You don’t want to do it.

The second and final third of the movie do a great job of pacing, piling on tension and terror with the quantity of any action movie. Even though you know they succeed, of course, the viewer still gets white-knuckled and breathless wondering how they will get out of another jam. The Czar noticed the millennial couple put away their phones, and one of them pitched forward in his seat during one scene, grabbed the back of the vacant seat in front of him, and kept muttering “Wow, wow, wow…” to the Czar’s evil delight. Yes, little Hunter, space travel is that freaking hard to do. Two millennials left that theater with a new sense of how awesome that World War II generation could be.

And the film makers often use saturated and grainy film to replicate the film stock of the era, to the extent that some scenes look exactly lifted from archived footage. It’s less distracting than it sounds, and really build authenticity.

Well, not all of it was perfect. The Czar found the music a little weak and even derivative. A pair of ships docking in space in time to a waltz? Where have we heard that before? A radio in the background plays a pop song right at its opening verses? Simplistic Moog arpeggios for orbital scenes and a big brass braaaaaam when the lunar landscape appears? Even John Williams would have been less clichéd than that.

Also uneven is the film’s perspective. Most of it takes place from the perspective of either Neil or Janet Armstrong—events that happen to others elsewhere are not shown, and the Armstrongs learn of them from phone calls, papers, and television—except, when the film makers put whole scenes shown from other characters’ points of view, which is a little off-rhythm, if you’re the sort of film viewer who even notices these things.

A third criticism is audio quality. Perhaps it was the theater’s aging sound system, but a lot of this movie involves astronaut’s peculiar accents being spoken through 1960s two-way radio technology, meaning that—in perilous scenes involving spacecraft—it was very difficult to understand the dialogue.

The Czar is reminded of two three things about Hollywood marketing.

First, all the folks who detest the Marvel movies and their pro-left messaging from Disney, which in fact is never evident in any of the Marvel Studios movies. In fact, when a leftist message is issued (Avengers 3, Captain America, Black Panther, and so on), it’s always by the bad guy. Right-wing fanaticism isn’t very attractive, and it makes a lot of people look stupid when someone rags on a movie they clearly haven’t seen. A lot of movies being mass-marketed today are fairly conservative if not rather libertarian in messaging.

Second, be careful with dire warnings about ham-fisted leftist attitudes in films. When Tadanobu Asano was cast as Hogun and Idris Elba was cast as Heimdall in Thor, we heard for two weeks how racist right-wingers were protesting the choices. Likewise, when John Boyega was cast as Finn in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, we heard how racist right-wingers were upset that a black actor was playing a lead role in the movie. As you likewise heard by now, and as exposed by then-blogger Stephen Miller, these racist protests were triggered by marketing executives in Hollywood to gin up fake controversy about the movie. The Czar suspects that the “they won’t even show an American flag” complaint about First Man may indeed be bait on a hook that a lot of people swallowed. In other words, people who knew it wasn’t true put it out there to show America how stupid conservatives are. And a lot of us bit that hook.

Oh, and a quick third thing. The astronaut Ed White of Apollo I is played in First Man by Jason Clark. This poor guy can’t get out of 1969, as he also played Ted Kennedy in Chappaquidick, which you should see right away. This screed isn’t a review of Chappaquidick, either, but wow—that movie is good, and destroys any positive legacy that the second-generation Kennedy family might have remaining.

Bottom line, First Man is utterly worth seeing, even on a small screen so that you can pause to look up whether or not some of these things happened (they did!), catch astronaut names, and figure out what their very interesting stories were as well. The anti-American vibe reported on social media is utterly without merit, and actor Ryan Gosling does a perfect impression of revealing what a frustratingly mellow person Armstrong really was, and how much fun Buzz Aldrin could be, often at the wrong times. The movie is not in any way a comedy, but a roller coaster ride of how incredibly Americans are when it really matters. Rather than sneer at this pseudo-controversy, sit back and enjoy the hell out of this movie.

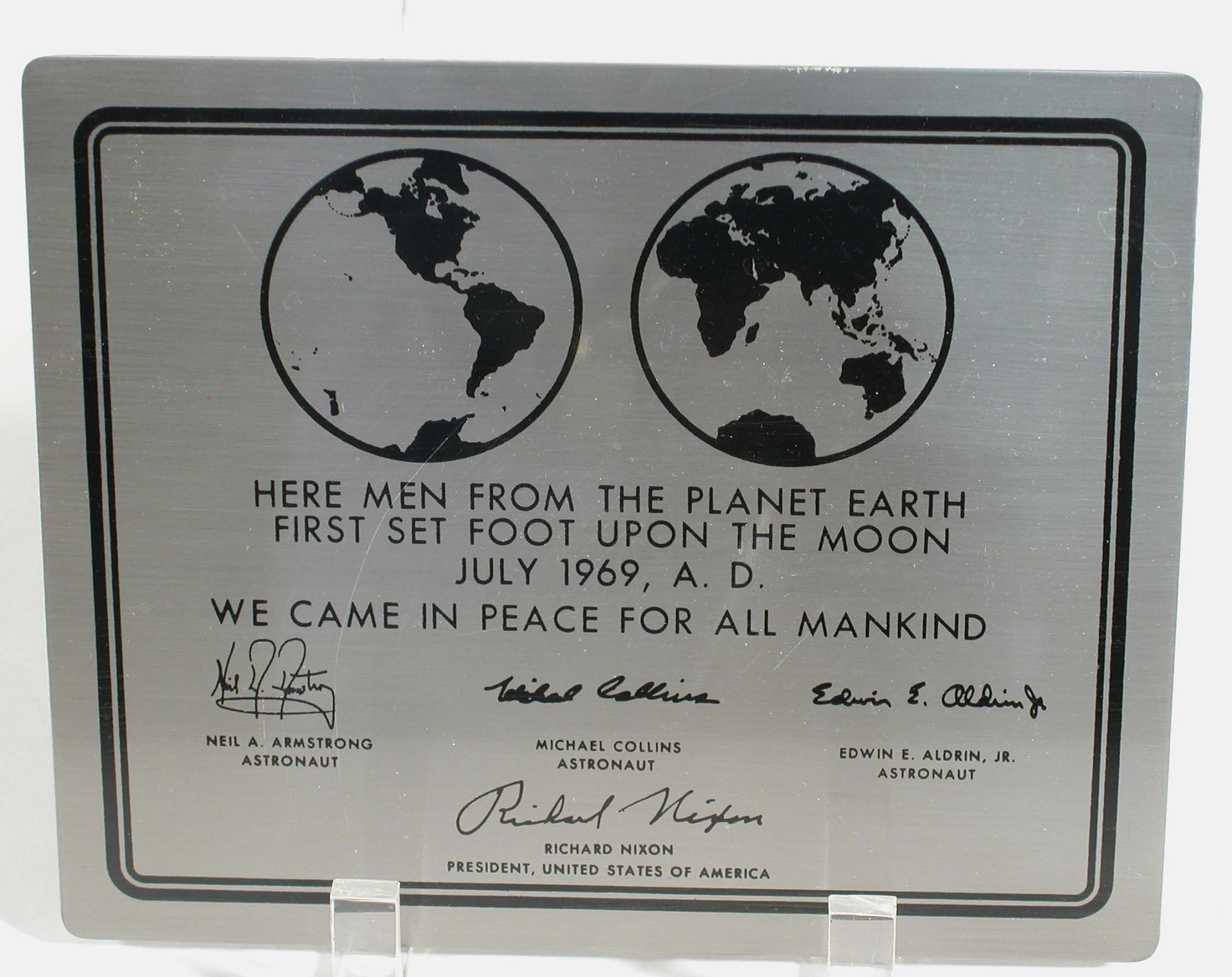

*Guess what? The film also skips over Aldrin setting up the camera, chatting with President Nixon, the two assembling and building the Lunar Laser Ranging Experiment (still providing useful data to this day), and setting up the solar wind experiment, which in fact they did long before they got around to wrestling with the flag. Nor does the film show them placing the plaque that promised our coming in peace for all mankind. Instead, the film focuses on Armstrong’s reaction to standing on another world for the first time in human history—which was the point of the movie.

Божію Поспѣшествующею Милостію Мы, Дима Грозный Императоръ и Самодержецъ Всероссiйскiй, цѣсарь Московскiй. The Czar was born in the steppes of Russia in 1267, and was cheated out of total control of all Russia upon the death of Boris Mikhailovich, who replaced Alexander Yaroslav Nevsky in 1263. However, in 1283, our Czar was passed over due to a clerical error and the rule of all Russia went to his second cousin Daniil (Даниил Александрович), whom Czar still resents. As a half-hearted apology, the Czar was awarded control over Muscovy, inconveniently located 5,000 miles away just outside Chicago. He now spends his time seething about this and writing about other stuff that bothers him.