Hi, everybody! As you know, we Gormogons love to grill, smoke, and cook outdoors, and we’re definitely well into that season, again. The Czar has already completed his self-appointed projects for the year (smoked pork chops, pizzas, flat breads, and so on), and was wondering what more he could do to help you folks out. Besides actually feeding you, of course.

Over the last couple years, the Czar has had many conversations with friends and neighbors about steaks. Doesn’t there seem to be a massive variety? The truth is that things aren’t so complicated—when you hit your local meat shop (for ‘Puter’s benefit, that’s a butcher, not a bar), you might be dizzied by the whole array of steaks available. Yikes, so many!

In fact, that’s not necessarily the case: there really are only about three main steaks, and two or three minor ones. The rest are all just different ways of cutting or selling the meat. As more people as us about this, the Czar realized a handy guide might be interesting.

How to Do Steaks

By now, regular readers know that any of the Gormogons will put a foot in your nuts if you light charcoals with lighter fluid. Seriously, don’t even think about using lighter fluid. Ever.

If you want to use charcoal, get yourself a chimney starter. You will be so glad you did. Any steak will cook beautifully over charcoal.

Surprisingly, you can cook steaks superbly over gas, too. The Czar uses either charcoal and gas as the mood strikes him. He might use charcoal with solid, flavored wood chunks if he’s hankering for something with a little side flavor. He will definitely use gas if cooking a large number of steaks—gas is unbeatable at producing consistent results across different pieces of meat.

The Czar will use one of two processes to do steaks.

One approach is to get the grill between 350° and 400° first, then sear the steaks as follows: five minutes on one side…then rotate the meat 90° and cook another five minutes. Then, flip the steak and repeat. Within 20 minutes, each steak will have crisscross grill marks and could potentially be ready to eat at medium rate. Thicker cuts, however, will require moving them to a safe zone and indirectly continuing to cook them indirectly so they finish up on the inside. The Czar looks for 150° to 155° internal temperature, and then he brings them into rest for 5 minutes before cutting.

The other method is to indirectly cook them first, letting the interior meat get all nice and medium-rare to medium. Then, when they’re about 130° to 140°, he will crank up the heat and sear them: a couple minutes, turn, couple minutes, flip, couple minutes, turn, a couple minutes. Then, as before, he brings them in to rest for 5 minutes. This method is ideal for really fat, monster-thick cuts, or when you have guests arriving late. You can slow-cook the steaks to ideal doneness, and then crisp up the outsides when the guests finally show up. Internal temperatures will be perfect at that point.

The results are about the same, but the strategy depends on circumstances. Don’t be afraid of either method, folks. If you’re seasoning, sprinkle the seasoning on just as the hit the grill, and just after you flip to get the other side. Don’t overseasons, and don’t keep flipping them like hamburgers. You should easily be able to complete steaks with just a single flip.

Major Steaks

Strip—This one is superb. Thick, but not too fatty. In fact, cook this with the fat left in it. During grilling, the fat will melt out, with the exception of the thicker ridge of fat on the outer curve (which you can easily carve off before serving). You can get these super-thick, so if that’s the case, use indirect cooking to get the centers where you want them. Based on how they’re cut, they might be sold as Kansas City Strips (bone inside) or New York Strips (no bone). These are great for parties, as they’re easy to cook to different levels of doneness on demand, and easily take on any rubs, seasonings, or sauces you want to try.

Strip—This one is superb. Thick, but not too fatty. In fact, cook this with the fat left in it. During grilling, the fat will melt out, with the exception of the thicker ridge of fat on the outer curve (which you can easily carve off before serving). You can get these super-thick, so if that’s the case, use indirect cooking to get the centers where you want them. Based on how they’re cut, they might be sold as Kansas City Strips (bone inside) or New York Strips (no bone). These are great for parties, as they’re easy to cook to different levels of doneness on demand, and easily take on any rubs, seasonings, or sauces you want to try.

Filet—These are smaller cuts, and can be very delicate; in fact, many meat eaters consider them mushy. The Czar doesn’t care for these rare, as they tend to be too soft and fleshy; he likes these medium to medium-rare. However, they are definitely easy to cook and popular to serve (“fancy!”), but cost may encourage you to limit their appearance at dinner parties. They can take on sauces, but you should keep these light or serve them on the side. There should be very little fat.

Filet—These are smaller cuts, and can be very delicate; in fact, many meat eaters consider them mushy. The Czar doesn’t care for these rare, as they tend to be too soft and fleshy; he likes these medium to medium-rare. However, they are definitely easy to cook and popular to serve (“fancy!”), but cost may encourage you to limit their appearance at dinner parties. They can take on sauces, but you should keep these light or serve them on the side. There should be very little fat.

Ribeye—Just awesome. These are generally flatter and thinner, and therefore cook more quickly. Look for marbled ones: too much fat, and they’re gristle. Too little fat, and they’re chewy and tough. These are easily served with no sauces or rubs—maybe just a little light seasoning. Don’t overcook these guys: medium is about as high as you should go, and all that fat in the middle will melt and turn to juice.

Ribeye—Just awesome. These are generally flatter and thinner, and therefore cook more quickly. Look for marbled ones: too much fat, and they’re gristle. Too little fat, and they’re chewy and tough. These are easily served with no sauces or rubs—maybe just a little light seasoning. Don’t overcook these guys: medium is about as high as you should go, and all that fat in the middle will melt and turn to juice.

Really, that’s about it. If you want to get technical, read on.

Minor Steaks

Skirt—This is a steak off the bottom of the beef. These are usually super-thin and long, so use care when cooking. They’re okay on their own, but really benefit from a wet sauce—the steak eagerly soaks up the marinade and holds its flavor well. These cook fast, so keep them moving on the grill! Don’t throw them on and walk away for a while, or you’ll overcook it badly. Slice these thinly and they’re ready for sandwiches, tacos, or tortas.

Flank—These need to be marinaded properly: slice gashes into both sides of the steak when raw, and then soak these in a great marinade for hours. Then, grill them up like you would a ribeye. Medium-rare is best, as the meat is soft and flavorful and not grotesquely bloody.

Sirloin—the sirloin is practically a class of steaks cut from the tenderloin of the beef. You actually need to be really, really careful when buying these because the word is applied, correctly, all over the place. Top sirloin is often nothing more than a really good strip steak. Sirloin steak is a cheaper cut, often with a lot of fat. Some cheaper sirloins are little more than marked-up roast meat, which are meant for your kitchen broiler more than the grill. Be skeptical of sirloin, no matter how pricey it is: if it looks like strip steak, go for it. If it looks like anything else, use caution.

Satellite Steaks

That’s the filet on the upper left, and the strip steak on the right of the T.

T-Bone—Nothing screams the 1950s like a good T-bone. And guess what? These can be fantastic because they’re two steaks in one. That’s right: the T-bone is a strip steak on one side of the T, and a filet on the other! That sounds superb, but use caution when choosing these for the grill. You don’t actually cook strips and filets to the same degree of doneness. A strip steak is better a little more rare, and a filet is good at medium. Maybe you disagree, but the odds are good you like that reversed. The point is that nobody likes both steaks cooked like one piece of meat. To do these right, you need to put one side closer to the heat and the other side away from the heat, and keep fretting over the internal temperatures. That way, you get the strip-side done the way you like strip steak, and the filet-side done the way you like filets. This can be a lot of work; or you can just buy thin ones and overcook them to leather. It’s really up to you.

Prime Rib—This is a rib roast, and is not a steak. You can cook it on the grill, of course, but do so as a roast—use indirect, slow cooking to bring out the flavor.

Hanger—Back in 1980, you could buy this scrap meat for a buck. Now, it’s super-expensive! The hanger steak actually connects some of the cow’s internal organs together. It sounds bad, but it’s really very good. Cook it like filet, with a little care and attention, and it will produce a soft, flavorful meat with breathtaking flavor. One of the Czar’s favorites, when he can find it cheap.

Flatiron—This is another cheap meat being sold for way more than it’s worth. It’s a flatter steak off the shoulder, and cook it like ribeye. Careful, as it’s gristly and can overcook quickly on you. The Czar doesn’t care for these except when cut super thin for sandwiches…but you can get better-textured meat for a lot less if that’s your plan.

Triangle—Not a steak, but trip-tip roast cut to look like one. You can get these all over the West Coast, and it can be harder to find east of there. Very low fat, so it can be chewy and tough if not carefully watched. This steak has a problem with uneven cooking, meaning one end tends to be medium-well while the other is rare. This can be useful if you like your steaks to different doneness, but it annoys the Czar. Let it cook indirectly first, and then sear it up (see our second method, above) for better results. This can cook fast, so be careful!

Tenderloin—Actually a whole class of meat in its own right, from which many other cuts and steaks originate. The whole tenderloin is an expensive mother, and will set you back a lot. It also can be easily ruined as the individual sections inside it might need to cook to different temperatures to be perfect. Tenderloins are a lot of work. Of course, a lot of cheap butchers might sell inferior meat as tenderloin because the inferior cuts technically originated there. Not a project for the beginner.

Bone-In Ribeye—Nothing more than a ribeye with a bone in it. Technically, these are cut from the lower thoracic vertebrae of the beef, and have a little sweetness in them from the bone marrow.

Delmonico—a boneless ribeye, named after the restaurant in New York City, which perfected a particular cut by which a section of fat is removed for a more uniform appearance.

Market—A ribeye.

Shell— A strip with a bone still attached.

Top Sirloin—A variant cut of strip steak.

Santa Maria—A marketing name for triangle (tri-tip) steak.

Top Loin—a strip steak, but from the best part of the loin.

Filet Mignon—A smaller piece of filet, with a little more flavor from being compact.

Châteaubriand—another non-steak. It’s a roast, from the tenderloin, and it’s quite large. You can grille it, but the cost alone should make you nervous about researching it first. The Czar’s never done one, and unless someone gives him one, he won’t ever bother.

Tournedo—as you cut the filet, it tends to get smaller along the length of the psoas major muscle. The tournedos are the smallest pieces at the very end of the muscle. Basically, tiny filets.

Porterhouse—A bigger T-bone, often with more filet than a regular T-bone.

Of course that’s not it! Marketing folks are drumming up new names all the time, and of course some chefs like to advertise French or increasingly Portuguese names for steaks. But beef is beef, and it all comes from the same places on the animal. If you see a steak not listed here, take a second to Google it and see what it really is, and whether it’s really worth $17 a pound.

If you’re solidly into triple-digit IQs, you’ve already seen a bunch of Jackie Chan movies. You understand they’re brilliantly directed, with hilarious scenes, literally death-defying stunts, and action that begs to be rewound and watched again. Did he seriously just do what it looked like he did?

If you’re solidly into triple-digit IQs, you’ve already seen a bunch of Jackie Chan movies. You understand they’re brilliantly directed, with hilarious scenes, literally death-defying stunts, and action that begs to be rewound and watched again. Did he seriously just do what it looked like he did?

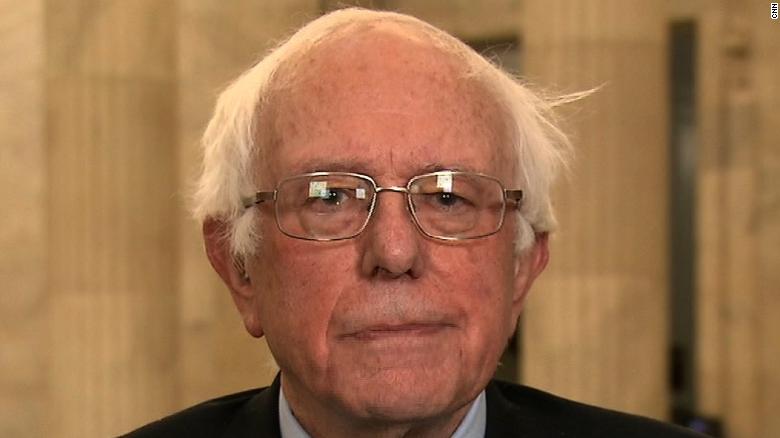

Senator Bernie Sanders gave a town hall rally to wildly enthusiastic supporters last night, allegedly moderated by the curiously incurious Wolf Blitzer on CNN. The Czar notes Wolf’s utter lack of interest in follow-up questions, taking Sanders’ word for everything.

Senator Bernie Sanders gave a town hall rally to wildly enthusiastic supporters last night, allegedly moderated by the curiously incurious Wolf Blitzer on CNN. The Czar notes Wolf’s utter lack of interest in follow-up questions, taking Sanders’ word for everything.

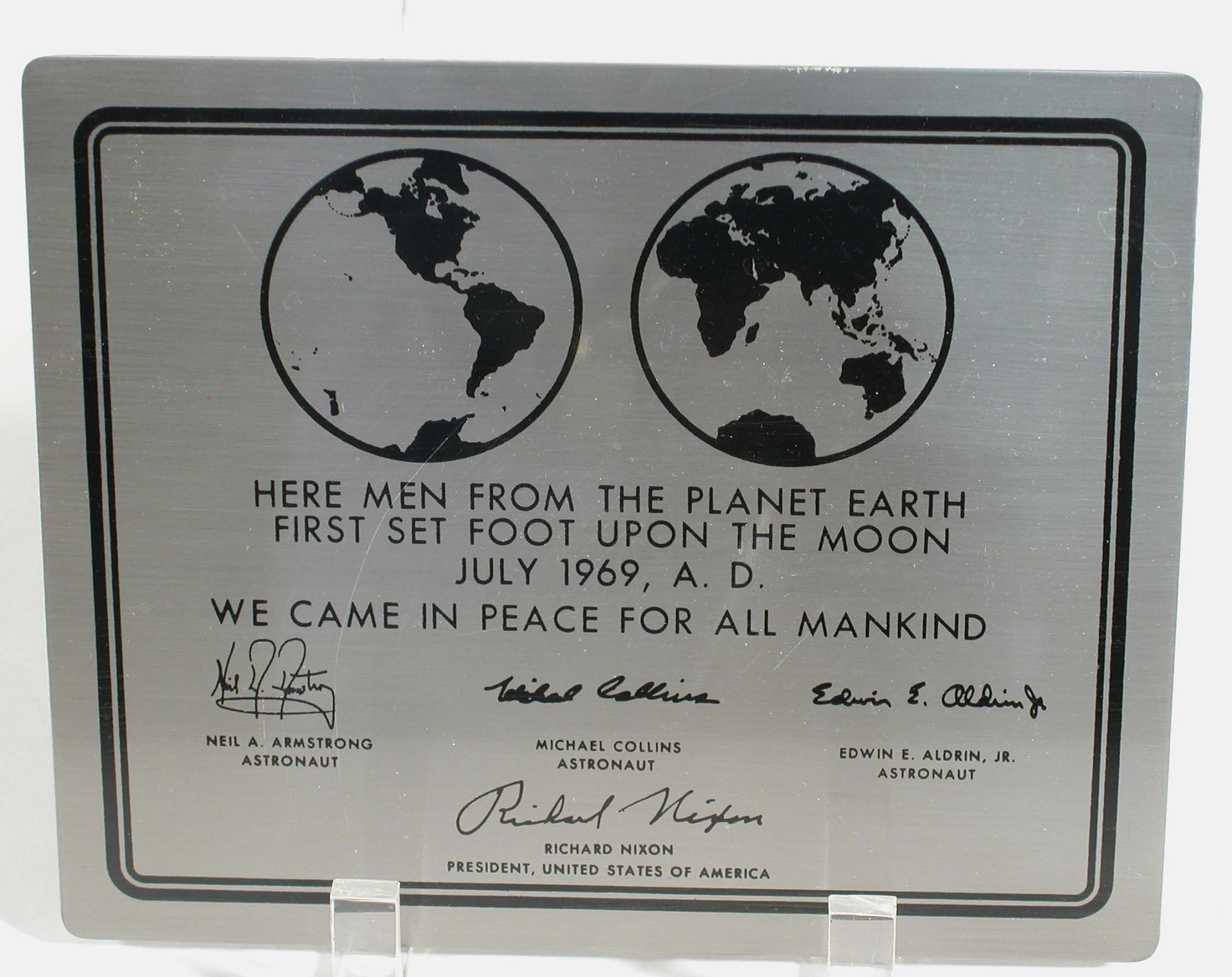

As the Czar discusses the Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, this will be less of a movie review and more of a jeremiad about social media.

As the Czar discusses the Neil Armstrong biopic First Man, this will be less of a movie review and more of a jeremiad about social media.

This is the sort of stuff that drives the Czar flipping crazy. So if you see serfs being flipped all over the dacha, today, you’ll understand the Czar is crazy. Today is probably a good day to steer clear of the dacha.

This is the sort of stuff that drives the Czar flipping crazy. So if you see serfs being flipped all over the dacha, today, you’ll understand the Czar is crazy. Today is probably a good day to steer clear of the dacha.

Dr. J is banging on my door trying to get me to update the scoring. Who knew he was so into soccer? Oh, wait, he told me to call it football. In the final rounds, teams advancing get 4, 8 and 16 points.

Dr. J is banging on my door trying to get me to update the scoring. Who knew he was so into soccer? Oh, wait, he told me to call it football. In the final rounds, teams advancing get 4, 8 and 16 points.

Strip—This one is superb. Thick, but not too fatty. In fact, cook this with the fat left in it. During grilling, the fat will melt out, with the exception of the thicker ridge of fat on the outer curve (which you can easily carve off before serving). You can get these super-thick, so if that’s the case, use indirect cooking to get the centers where you want them. Based on how they’re cut, they might be sold as Kansas City Strips (bone inside) or New York Strips (no bone). These are great for parties, as they’re easy to cook to different levels of doneness on demand, and easily take on any rubs, seasonings, or sauces you want to try.

Strip—This one is superb. Thick, but not too fatty. In fact, cook this with the fat left in it. During grilling, the fat will melt out, with the exception of the thicker ridge of fat on the outer curve (which you can easily carve off before serving). You can get these super-thick, so if that’s the case, use indirect cooking to get the centers where you want them. Based on how they’re cut, they might be sold as Kansas City Strips (bone inside) or New York Strips (no bone). These are great for parties, as they’re easy to cook to different levels of doneness on demand, and easily take on any rubs, seasonings, or sauces you want to try. Filet—These are smaller cuts, and can be very delicate; in fact, many meat eaters consider them mushy. The Czar doesn’t care for these rare, as they tend to be too soft and fleshy; he likes these medium to medium-rare. However, they are definitely easy to cook and popular to serve (“fancy!”), but cost may encourage you to limit their appearance at dinner parties. They can take on sauces, but you should keep these light or serve them on the side. There should be very little fat.

Filet—These are smaller cuts, and can be very delicate; in fact, many meat eaters consider them mushy. The Czar doesn’t care for these rare, as they tend to be too soft and fleshy; he likes these medium to medium-rare. However, they are definitely easy to cook and popular to serve (“fancy!”), but cost may encourage you to limit their appearance at dinner parties. They can take on sauces, but you should keep these light or serve them on the side. There should be very little fat. Ribeye—Just awesome. These are generally flatter and thinner, and therefore cook more quickly. Look for marbled ones: too much fat, and they’re gristle. Too little fat, and they’re chewy and tough. These are easily served with no sauces or rubs—maybe just a little light seasoning. Don’t overcook these guys: medium is about as high as you should go, and all that fat in the middle will melt and turn to juice.

Ribeye—Just awesome. These are generally flatter and thinner, and therefore cook more quickly. Look for marbled ones: too much fat, and they’re gristle. Too little fat, and they’re chewy and tough. These are easily served with no sauces or rubs—maybe just a little light seasoning. Don’t overcook these guys: medium is about as high as you should go, and all that fat in the middle will melt and turn to juice.

Colombia

Colombia As you have heard, the GOP is in about the worst shape imaginable for the 2018 elections. The only party facing worse odds is the Democrat party. The long-promised blue tsunami might be a small puddle in some areas.

As you have heard, the GOP is in about the worst shape imaginable for the 2018 elections. The only party facing worse odds is the Democrat party. The long-promised blue tsunami might be a small puddle in some areas. In fact, about the only negative thing you’ll read about Democrats is concern about voter apathy. Possibly the only accurate prediction the media have made is that the winner of the 2018 elections—Republican or Democrat—will be decided on which party had less voter apathy. Truth is, many Democrats don’t care about voting in the Age of Trump, since civilization is doomed anyway. And many Republicans don’t care about voting because Hillary Clinton isn’t running. That they know of.

In fact, about the only negative thing you’ll read about Democrats is concern about voter apathy. Possibly the only accurate prediction the media have made is that the winner of the 2018 elections—Republican or Democrat—will be decided on which party had less voter apathy. Truth is, many Democrats don’t care about voting in the Age of Trump, since civilization is doomed anyway. And many Republicans don’t care about voting because Hillary Clinton isn’t running. That they know of.

Here’s the thing: the Supreme Court doesn’t pick a winner and a loser. They determine whether the Constitution is affected negatively by the decision. This is a big difference: they’re not a court of appeals, but a referee to see if the rules were correctly applied or not.

Here’s the thing: the Supreme Court doesn’t pick a winner and a loser. They determine whether the Constitution is affected negatively by the decision. This is a big difference: they’re not a court of appeals, but a referee to see if the rules were correctly applied or not. What happens then?

What happens then? So someone in the Supreme Court will write the majority opinion, in which he or she tries to explain in simple language the most byzantine account of why they are the majority. See, all the good cases are gone: British troops aren’t being quartered anymore, and slavery was finally wiped out, so now we get Justice Stephens trying to explain Obamacare isn’t really a tax, even though it is a tax, and that taxes need to come from the House, except this didn’t because it wasn’t really the tax he just said it was.

So someone in the Supreme Court will write the majority opinion, in which he or she tries to explain in simple language the most byzantine account of why they are the majority. See, all the good cases are gone: British troops aren’t being quartered anymore, and slavery was finally wiped out, so now we get Justice Stephens trying to explain Obamacare isn’t really a tax, even though it is a tax, and that taxes need to come from the House, except this didn’t because it wasn’t really the tax he just said it was.